Hayward Gallery

7 Feb 2024 – 6 May 2024

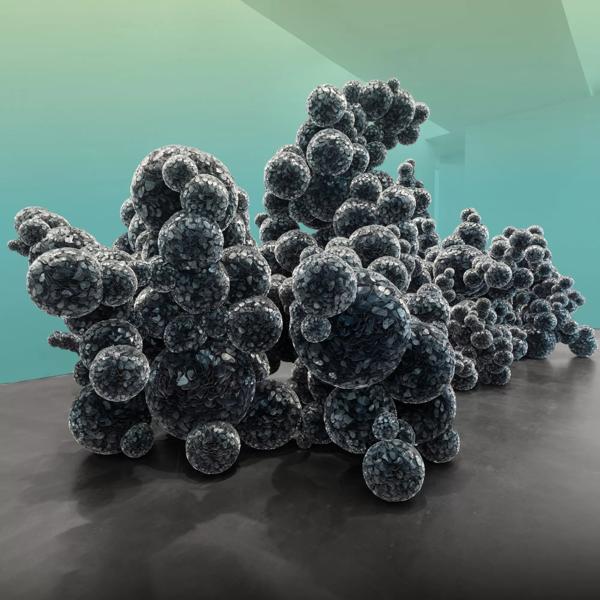

When Forms Come Alive

The Hayward Gallery’s new exhibition, exploring sixty years of restless sculptureTara Donovan, Untitled (Mylar) 2011/2018 Mylar and hot glue Dimensions Variable Installation view, MCA Denver Photo: Christopher Burke Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery. 11 Jun – 1 Sep

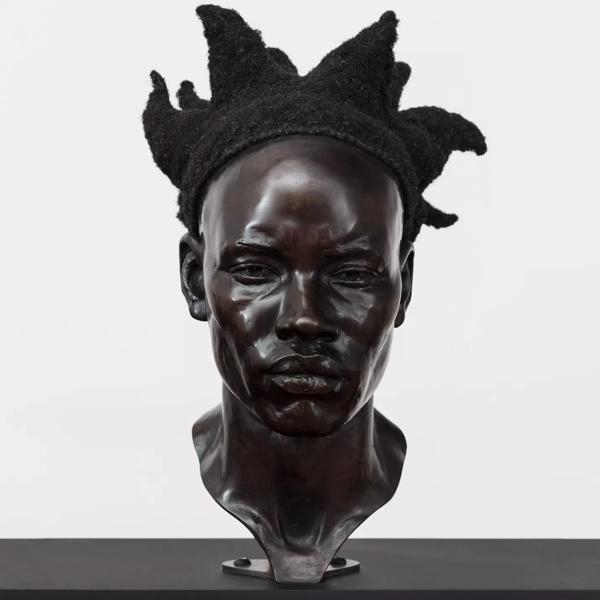

Tavares Strachan: There Is Light Somewhere

An artist of lost stories shines a light on unsung trailblazers and hidden historiesTavares Strachan, A Map of the Crown (Congo Candle Wick), 2022. Bronze, human hair, wood. 69 3/4 x 23 5/8 x 23 5/8 in. (177 x 59.9 x 59.9 cm). Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Claire Dorn.

A world-renowned contemporary art gallery and a landmark of brutalist architecture

The Hayward Gallery's year-round exhibition programme focuses on presenting a wide range of adventurous and influential artists from across the world.

Visitor info

Our number one priority is the health and wellbeing of our visitors and staff.

Tue – Fri, 10am – 6pm

Sat, 10am – 8pm

Sun, 10am – 6pm

Closed Mon

The gallery will be open 10am – 6pm on Monday 6 May 2024

Our address is: Hayward Gallery, Belvedere Road, London SE1 8XX.

- The nearest tube and train stations within 5-7 minutes walk are Waterloo (Northern, Bakerloo, Jubilee and Waterloo & City lines) and Embankment (District & Circle lines).

- There are also lots of bus routes with stops 2-5 minutes from our venues. For more information on getting here by road, rail or river.

We recommend booking your tickets online in advance. Booking fees apply online (£3.50) and over the phone (£4). Booking fees for Hayward Gallery tickets are £3 online and £3.50 over the phone. There are no booking fees for in-person bookings, Southbank Centre Members and Supporters Circles.

If you are a Member or supporter, please book your ticket online (details of how to book these tickets are below).

Once you’ve booked, we’ll send you an e-ticket. There’s no need to print your e-ticket – just show your phone to our hosts on entry to the gallery.

Some free events, including our HENI Project Space exhibitions, don't require a pre-booked ticket – you can simply turn up on the day. These events are labelled FREE on our website with no way to book.

If you don't receive your e-ticket

Check your spam folder for an email from [email protected]. If you don’t receive your e-ticket within a few hours of booking, please get in touch.

Members

If you are a Member or supporter, you can book your ticket online in advance by selecting the 'Members’ free ticket' option under the concessions tab. Any extra tickets will be priced at the standard rate unless another concession applies.

Dual Members must book their tickets separately.

Lambeth residents

Lambeth resident tickets for Tue – Fri and after 5pm on Saturdays are £8. Tickets must be booked in advance via our website by selecting the 'Lambeth residents' ticket type under the concessions tab. ID may be requested on arrival.

Under-30s

Under-30s tickets for Tue – Fri and after 5pm on Saturdays are £8. Tickets must be booked in advance via our website by selecting the 'Under 30' ticket type under the concessions tab. ID may be requested on arrival.

Under-12s

Under-12s tickets are free. Tickets must be booked in advance via our website by selecting the 'Under 12' ticket type under the concessions tab. ID may be requested on arrival.

Reciprocal tickets

Reciprocal tickets for the Hayward Gallery can be booked via email for any weekday and after 5pm on Saturdays, excluding the first week and final two weeks of the show. Currently pre-booking is essential. Please remember to bring valid ID with you when you visit.

Museums Association and ICOM

Members of the Museums Association and ICOM can get one free ticket. Tickets must be booked in advance by emailing us, giving the date and time you would like to visit the gallery. Please remember to bring valid ID with you when you visit.

Group rates

For group bookings of ten or over, tickets are £15 each (group rate available Tuesday – Friday). Group bookings must be made in advance on 020 3879 9555 or via email.

We are happy to welcome primary, secondary and SEND schools during Hayward Gallery opening hours at the following rates:

Primary schools: Free, booking required.

Secondary schools in Lambeth and Southwark: Free, booking required.

All other secondary schools: £8 per pupil. Accompanying teachers go free.

Please note that 15 students is the maximum number that we can accommodate in one group per timed session.

Please email us with your preferred visit date and any other relevant school and pupil information at [email protected]

If you have any further questions or need anything else to support your visit, please contact the schools team.

When you arrive

Entrance to the exhibition is via the Hayward Gallery main entrance. We’re operating a one-way system.

Get here as close to your time slot as possible – you won’t be able to come into the Hayward Gallery to wait.

Toilets

Toilets, including accessible toilets, are open for ticket holders in the Hayward Gallery Foyer.

Cloakroom

Our cloakroom is £1 per item and is for coats, umbrellas and small bags. You won’t be able to bring any bags over 40 x 25 x 25cm into the exhibition, so please leave large bags at home.

Visitors with prams, buggies and wheelchairs are welcome.

Shop

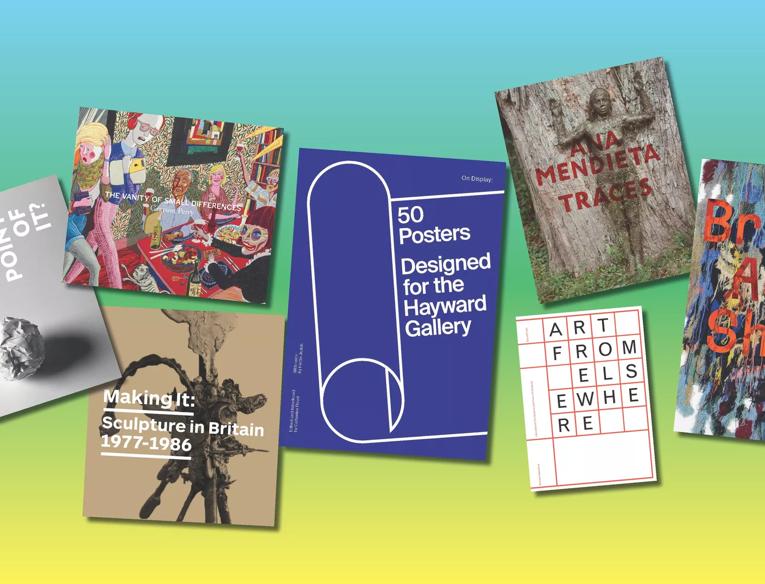

After leaving the exhibition, the one-way system takes you through the Hayward Gallery Shop, which is now cash-free.

We're cash-free

Please note that we're unable to accept cash payments across our site.

When you arrive

For step-free access to the Hayward Gallery from the Queen Elizabeth Hall Slip Road, please use the Hayward Gallery car park lift.

There may be short queues to enter the building and the exhibition. If you are not able to queue or need further assistance, our hosts are here to help you.

More about Access & facilities

Inside the gallery

Accessible toilets are available, and there is some seating for visitors who need it during their visit.

We welcome wheelchair users and guide companion dogs. Wheelchairs and gallery stools are available for visitors by speaking to a host when you arrive (subject to availability).

Our Access Scheme

If you’re signed up to our Access Scheme, you’re eligible to bring a companion free of charge. Please book a standard ticket and email us to add your companion to your booking. If you are unable to book online, please get in touch.

Parking

Blue Badge holders and those with access requirements can be dropped off on the Queen Elizabeth Hall Slip Road off Belvedere Road (the road between the Royal Festival Hall and the Hayward Gallery).

There are four Blue Badge parking spaces available for visitors located on the Queen Elizabeth Hall Slip Road. Spaces are allocated on a first-come, first-served basis, and use of them is free. You are required to display your Blue Badge as you enter the site. Vehicles that do not display a Blue Badge are refused entry.

Blue Badge parking at National Theatre

Alternative parking for Blue Badge holders visiting the Southbank Centre can be found at the National Theatre car park (330 metres). If you are visiting the Hayward Gallery, just take your badge and car park ticket to the Ticket Desk in the gallery foyer for validation before you leave.

Please note: on Sunday when the National Theatre building is closed there is no step-free access from the car park.

Alternative parking is available nearby at the APCOA Cornwall Road Car Park (490 metres), subject to charges.

Blue Badge parking APCOA Cornwall Road

Alternative parking for Blue Badge holders visiting the Southbank Centre can also be found at the South Bank Car Park – APCOA Cornwall Road Car Park. Just take your badge and car park ticket to the parking attendant office at the entrance to the car park for validation before you leave.

A drop-off point at the Royal Festival Hall (30 metres) has been created for visitors who are unable to walk from alternative car parks.

The Hayward Gallery Cafe is the ideal spot for some pre-exhibition sustenance or a post-visit drink.

Drop in for a speciality coffee, artisan sandwiches, seasonal fresh salads and an array of homemade cakes and pastries from our in-house baker. Soak up the views with a crisp glass of wine, locally sourced craft ale or one of our signature cocktails.

And there are even more options around our site, including restaurants, cafes and our Southbank Centre Food Market.

Members get more

Want to keep your contemporary art appetite well fed year round? Members get free entry to Hayward Gallery plus invites to exhibition private views.